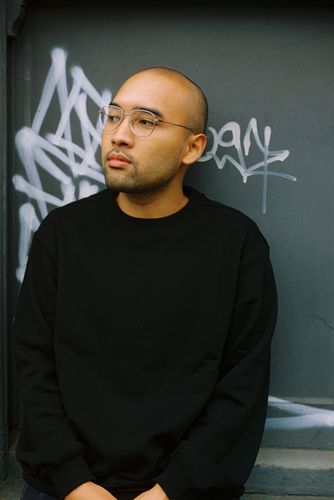

This post was originally published in The Urban Condition by Aushaf Widisto (aka Oswald / Oz), who is an aspiring Urbanist, Writer, and Cultural Researcher based in Melbourne, Australia. It's a great introduction for urban planning, whether you're already in the industry or not.

“A city is more than a place in space, it is a drama in time.” ― Patrick Geddes

In 2007, the world’s urban population surpassed its rural counterpart. This occurrence marked a major turning point in the history of human civilization. More than half of the entire human species — that’s approximately 4 billion people — now lives in urban areas.

Cities are now, officially, the most human place on earth.

This knowledge then poses a crucial question: What should we do with our cities? The flow of urbanization shows no sign of halting. Cities will continue to grow, and that unceasing growth can work for or against us. It doesn’t take a lively imagination to understand that the future of humanity, and perhaps that of planet earth, depends on how we shape our cities.

Shaping cities to accommodate human life — this is by no means an easy task. Fortunately, we have just the toolkit to address it.

It’s called urban planning.

About Urban Planning

Urban planning, sometimes also “city planning” or “town planning,” is an interdisciplinary field that studies urban areas and how we can purposefully direct their development, to create cities that are organized, attractive, and — most importantly — livable.

American Planning Association defined it as follows:

“[…] a dynamic profession that works to improve the welfare of people and their communities by creating more convenient, equitable, healthful, efficient, and attractive places for present and future generations.”

McGill University in Canada proposed a more pragmatic definition, which perhaps is more relevant to the present-day context:

“[…] a technical and political process concerned with the welfare of people, control of the use of land, design of the urban environment including transportation and communication networks, and protection and enhancement of the natural environment.”

As mentioned, this intricate field combines a multitude of aspects, from the technical and tangible ones like land use, infrastructure, and transportation systems, all the way to their more abstract counterparts like socio-cultural demographics, regional economy, and public policy.

Cities are complex entities, and thus urban planners must consider all these elements to accommodate the interests of various stakeholders, public and private alike. When planning cities, simpler is rarely (if ever) better, as the answer to every problem tends to be multilayered and multifaceted.

Moreover, while urban planning is considered a distinct field, it is closely related to urban design, placemaking, architecture, landscape architecture, and other fields cognate to urban studies or spatial sciences. Experts from these fields often collaborate on the same projects, as their skill-sets closely intersect with each other and therefore work to solve the same problems.

Across history, notable figures in the urban planning field (who aren’t all necessarily urban planners by trade) include Patrick Geddes, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Ebenezer Howard, Jane Jacobs, and William H. Whyte.

Why (and How to) Plan Cities?

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”— Jane Jacobs

In the beginning, we’ve established the reason why we need to plan cities: Because their importance in our lives will only grow as time progresses. The way civilization develops will influence and be influenced by the cities we live in, and our fate as a species will inevitably go along with it.

Urban planning gives us a way to affect this process in a way that benefits us. As Jane Jacobs said, humans make cities, and it is humans that cities must cater to — because, as we shape our cities, they will shape us in return. And we want to make sure they’ll shape us the right way.

This human-centric approach to urban planning seems obvious at first, but it really isn’t. If we only look at the recent history of human civilization, we’ll see that often the central subject in urban planning is not humans. Instead, it’s tall buildings and automobiles. The evidence for this is clear in many places: Capitalistic interests often outweigh humanistic interests.

Granted, things are starting to change. But it took us several decades to see the wrong in our ways, and therefore, often the most challenging problem that urban planners need to solve — to put bluntly — is “fixing the mistakes of our predecessors” instead of “starting from the ground-up.”

Planning for expedience doesn’t work anymore. It’s like trading the future for the present. Instead, we must plan for sustainability, as advocated by the UN through their 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — so we can leave boons, not banes, for our successors.

Plan residential areas so everyone has access to housing. Plan commercial zones so economic activities benefit all parties. Plan transportation networks so people can traverse their city with ease. Plan green spaces so the environment and humans can thrive in coexistence.

Plan everything. Bring utopia as close to reality as possible.

That is the raison d’être of urban planning — oversimplified. As we’ve established before, urban planning solutions are rarely simple. Reality is always more complicated than we’d like it to be, even more so with gargantuan entities like cities. There will always be compromises to make. There will always be imperfections we have to live with.

Is the task futile, then? No, not exactly. Urban planning is not a fool’s errand. If it is, we wouldn’t have beautiful urbanscapes like London and Paris. We wouldn’t have majestic metropolises like Tokyo, Sydney, and New York. Not even peaceful capitals like Oslo and Copenhagen.

These cities are by no means perfect. They have flaws, both slight and striking — but still, in their existence, we can observe tangible proof that urban planning works, and that it is a fight worth getting into.

Conclusion: Humanity vs Urbanity

Cities are now the most human place on earth. The statistics don’t lie, and yet, some people may argue that cities are humane in numbers only, not in character. Urban dwellers are materialistic and individualistic, they say — but that’s oversimplifying, and again, anything oversimplified is seldom true.

Despite all the negative traits associated with cities, humans are drawn to them. We keep marching toward cities, settle down in their corners, and call them home. This is a worldwide and species-specific trend. Humankind and cities go hand-in-hand. Or, at least, they’re supposed to.

And that’s the mission: Making sure they go hand-in-hand.

Therefore, the importance of urban planning cannot be overstated. In the beginning, we shape cities. We plan, design, and develop them to fit our image. But in the long run, our cities shape us. Our houses decide how we live. Our streets affect how we walk. Our parks influence how we play.

Over time, our cities form who we are: Our identity, personality, even our emotions. As long as humankind lives in cities, they will become part of us, both as individuals and as a species. The relationship between humanity and urbanity doesn’t have to be antagonistic. We can make it symbiotic instead.

Planning cities means planning the fate of our species, and it takes tremendous wisdom to carry out that Herculean (or even Sisyphean) task.

As said by Socrates the philosopher:

“By far the greatest and most admirable form of wisdom is that needed to plan and beautify cities and human communities.”

Urban planners, your work matters. Do it wisely.

Aushaf is an aspiring Urbanist, Writer, and Cultural Researcher based in Melbourne, Australia. Having studied Urban & Regional Planning at Institut Teknologi Bandung and Cultural & Creative Industries at Monash University, he combines these two disciplines to specialize in Creative City Planning, Placemaking, and Arts/Culture-led Regeneration. Ultimately, his goal is to leverage arts and culture to create better cities and communities. Some of Aushaf’s work can be found on his Medium page, where he also manages an urbanism publication called The Urban Condition.