This essay was written by Dr John Guy Perrem, who is an urban geographer and educator. Follow his work on Urban Space Initiative, Twitter, and his personal photography website.

The response to COVID-19 has seen a sharp decrease in the everyday urban mobility of children and young people throughout Japan, combined with reduced opportunities for them to socialize in public spaces. Mandatory school closures along with concerns over contracting COVID-19 in communal city spaces such as parks have been the driving forces behind curtailing mobility beyond the domestic sphere. While the steps taken to reduce the risk of infection are rooted in good intentions, it raises questions about the daily experiences of children and young people during the crisis who now find themselves in an existence with significantly reduced mobility. Additionally, children’s own perceptions of the virus and its impact on their lives have been underexplored and largely underrepresented in the media.

Due to both the high number of days spent in school throughout the year and the long hours each day, schools are a crucial social space as well as educational platform for children living in cities in Japan. The sudden national closure of schools in an effort to curtail the spread of COVID-19 has consequently rapidly removed this social hub from students’ lives.

Beyond the closure of schools, children in Japan have also been impacted by a loss of available public space, and by official, institutional, and parental barriers. In Kanagawa, parents, schools, and the police band together to set boundaries for children, creating restrictions on mobility which are self-reinforcing and complex. Parents think that society was safer in the past, and so concepts like fear of outsiders — i.e. “stranger danger” — kept kids locked down even before the outbreak of the virus. I found that what public space ‘is’ and who it is ‘for’ could become hegemonic and that systems of protection can ultimately serve to exclude and act as barriers to the very subjects they sought to guard: children.

As an educator currently working in Japan who undertook PhD fieldwork in Kanagawa, I was able to draw upon a parental network to interview students and their family members. The interviews were conducted to explore the impact COVID-19 had on their daily mobility and their feelings about it in an effort to shed some light on their experiences.

Nana, a 14 year old student whose grandmother lives with her family stated that,

“I feel trapped inside because everyone is saying that the virus is so dangerous. And I don’t want to make my grandmother sick. I can call my friends but it’s different, I miss seeing them in person and going to the park,”

The park in question is a large seaside amenity in Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture, one in which I had previously conducted observational research. Kanagawa, and its famous capital Yokohama, sit directly south of Tokyo and form part of the Greater Tokyo Area through largely unbroken urban development. My rationale for the selection of the fieldwork site in Kanagawa was due to the park being identified as an important platform within interviews previously conducted with parents, teachers and students at a school in the area. The interviews in this article substantiate the argument of how important urban public space mobilites are for young people and the sense of loss and confinement they feel when that option is removed. The scale of this removal poses a unique challenge for young people and public space in the face of COVID-19. The experiences presented herein therefore represent new perspectives in unknown territory and the unfolding relationships between people and public space at an exceptionally challenging time.

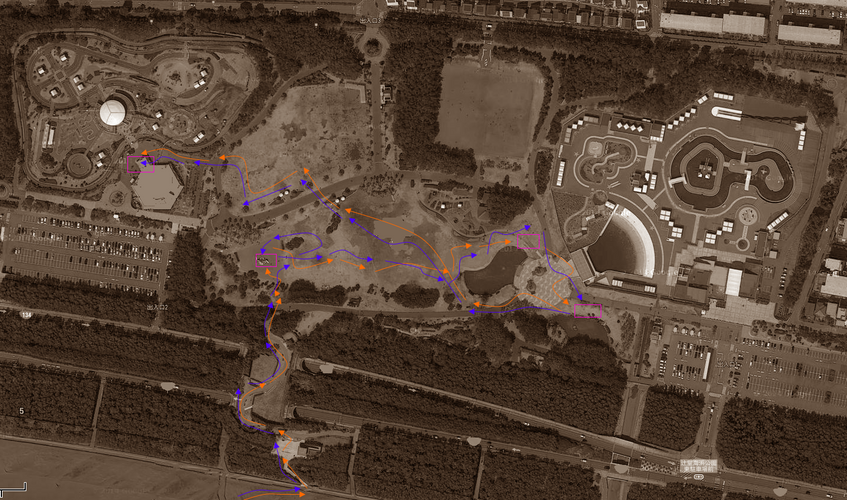

Part of this fieldwork included trajectory mapping, which showed the varied paths taken through the space in both independent and accompanied mobilities. The absence of children and young people, and thus an absence of mobilities, was very striking when I returned there during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Nana’s mother Yuko expounded that, “I’ve asked Nana to stay home as much as possible. I don’t feel guilty about it. We have to stop the virus and it’s a small sacrifice for her to make, but I am concerned about her education. I don’t know when she can return to classes.”

Figure 1: Park trajectories for two teenagers engaged in exploratory mobilities.

This feeling of being trapped was shared by another student named Sei. ‘‘My favorite café is right across the street from our house, but father said I can’t go there. I can’t get much fresh air outside; I’m starting to hate my house. I hope it will all end soon so I can do normal things again’’.

Sei’s father, Shunsuke, took a sympathetic view of his daughter’s regulated situation, yet he was firm that until the COVID-19 threat had passed, her movements would continue to be restricted. ‘‘I’m worried about Sei; I can see she is very unhappy when I come home from work each night. If she gets sick I would not forgive myself, so I can accept that she is angry with me about it. It makes life at home quite difficult’’.

Figure 2: Park trajectories for a mother and daughter indicating more logical loop mobility.

Beyond only mobility, COVID-19 has also provoked unfounded spikes in racism against people from Asia or who are Asian in appearance in multiple countries as fears mount over the spreading virus and its current status as a pandemic. The geographical spread of this racism is wide-reaching and has encompassed cities such as London and New York. The process of viewing minorities as responsible or as ‘other’ in times of crisis is an unfortunately common occurrence and Japan is not completely immune to this phenomenon.

Ryusei, a 15 year old student who has a Chinese mother and Japanese father described his experience in relation to reading racist comments online. His experience went beyond feelings of confinement and into something more painful and personal. ‘‘Recently I saw many bad things written about Chinese people online and when I went to the convenience store near the train station people were talking about it. I don’t think it’s fair. This isn’t just a Chinese problem. We should help each other. I feel angry if someone thinks my mother is responsible just because she is Chinese. It’s crazy’’. Ryusei’s mother didn’t wish to comment on the current situation.

Figure 3: Park without trajectories of park users showing the absence of social usage.

From the preceding accounts, it is clear that the response to COVID-19 has meaningful implications for children, young people and their parents living in cities in Japan across a host of issues. These should not be discounted, because if the situation continues to deteriorate and schools remain closed, millions of students will have to manage a diminished social life in the city, plus strictly curtailed mobility. Others, like Ryusei, will have to navigate the additional challenges of identity and belonging in sometimes socially challenging environments. To combat the potential negative consequences of school closures beyond education, a proactive approach is required, placing the needs of social contact and inclusive urban community bonding as a priority.

A concrete suggestion I propose is establishing new neighborhood support networks throughout urban areas to enable children and young people to have access to parks via a block rota system. This system could be used inclusively throughout each day in tandem with proper social distancing to provide mobility and a degree of freedom through independent trajectories within designated park areas, playgrounds or outdoor school sports grounds. This ability to roam within a set time frame could counteract the emerging unhealthy sense of enclosure. The block rota system would have the added benefit of staggering park usage and thus reduce the density of users to an even flow. I propose a second proactive communal layer could also be added where young people then communicate and share their daily experiences of using the public spaces. This could be accomplished through using a class or school network via online platforms and allow for connecitons and interactions to be consistently maintained with diverse individuals outside the family unit.

COVID-19 has the potential to alter relations between people and public spaces in fundamental ways. My research has already seen elements of this shift in ongoing work with guerilla gardeners whose activties are taking on new and inventive forms for example. The future of research on urban public space as well as the activities of the general public will necessitate evolution in unforseen ways but with some ingenuity public spaces don't need to be abandoned yet.

Dr John Guy Perrem is an urban geographer and educator. He attained his PhD from the Dept. of Social and Economic Geography at Uppsala University in 2016. Prior to that he obtained an MPhil from the Dept. of Geography at Univeristy College Cork and a Postgraduate Diploma in Education from University College Dublin. He is currently an affiliate member of the Education, Migration and Segregation (EMS) interdisciplinary research network led by Dr Håkan Forsberg of the Dept. of Education at Uppsala University. Outside of the academy he has worked in a planning and architectural firm and as an educator. Additionally, he established the Urban Space Initiative in a voluntary capacity to undertake diverse small scale research and activism for championing urban public space. He is a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society (RGS) with the Institute of British Geographers.