This essay was written by architect and journalist Amnon Direktor, who is originally from Israel and now based in Brussels, Belgium. Follow his work on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Gas lamps in Belfast, Northern Ireland (Credit — Wikipedia).jpg

How would you react if you were told that the wooden bench in your city is assigned for strict preservation? And will it surprise you that there is a proposal to turn the city's garbage bins into a city icon? You would probably have smiled and thought it was some kind of joke. After all, only one-of-a-kind buildings are meant for preservation, so what does that have to do with a street bench and a trash bin?

Preservation in the context of cities is usually focused on historical buildings and sites, those that contain within them cultural, historical and architectural values. In relation to them, the preservation of the heritage of street furniture may be portrayed as a somewhat esoteric matter, which may even contradict the essence of preservation, which is associated with exclusivity. Whereas urban furniture and objects are scattered throughout the city, replicated, and most of them, most likely, are transparent to us. We take them for granted. Nevertheless, despite their prevalence, and perhaps precisely because of it, these objects and furniture play an important role in city life and are worthy of complex thought as to how they are preserved and to their heritage. The first question that is asked, then, is what is the importance of street furniture and why should it be preserved in the urban space?

Each city is unique in its own way. The uniqueness can be expressed in a specific building style, history and local heritage, in a particular climate or in a unique topography. Each city has its own characteristics, on which its reputation is based. The buildings in Jodhpur in northwestern India, for example, are all painted blue; In Jerusalem, the buildings are required to be covered with ‘Jerusalem stone’ as part of the city's historical master plan; In Porto, painted ceramic tiles called Azulejo cover the facade of many buildings. Along with these special characteristics, which make a city a tourist attraction, every urban landscape also includes street furniture and various objects that even if they do not get to be mentioned in tourist guides, are an integral part of the city. In the main streets, squares and parks, and in fact, in all areas defined as public, there are light poles, bus stops, benches or trash bins. A city without street furniture is not a city; Or in other words: what is urbanity without benches, trash bins and street pillars?

Capela de Santa Catarina, Porto, Portugal (Credit — Nelson Rocha, 2009)

The definition of street furniture applies to a system of fixed objects located throughout the city for various purposes — these are the everyday products of urban life. The term was first formally defined in the 1950s: "Street furniture is all the elements that are placed in public spaces by the authorities and serve the public. They can be permanent or temporary, functional or for ornamental purposes”. The definition includes a very wide range of furniture and useful aids, for example, benches, traffic barriers, mailboxes, telephone booths, street lights, traffic lights, traffic signs, tables, street signs, bus stops, and more. The design and location of street furniture take into account functionality, visual identity, pedestrian mobility and road safety. Street furniture is created for the purpose of rest, sitting and eating, all of which are functions of great importance for the elderly, the disabled or people with children. But in addition to their functional aspect, urban furniture items, such as benches and tables in parks, can be socially significant for a wider audience as well: they provide comfort and create a leisure atmosphere. Properly designed furniture in the right places motivates people to leave the house and makes them feel welcome and relaxed.

The history and development of street furniture from ancient history to the modern era

It is difficult to produce a sufficient material history in the field of street furniture precisely because of the properties of urban furniture: as they are portable and replaceable, and perhaps also because they were never considered worthy of preservation, few remains are left. The earliest examples of street furniture were identified in stone samples in excavations carried out in areas belonging to ancient cultures such as the Maya in Mesoamerica, the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan and the ancient city of Pompeii in southern Italy. Among this ancient street furniture were elements that direct the movement of people in public areas such as signs made of stone, buildings intended for sitting, manure pits and signs made by carved on stone slabs. Simultaneously with the changes that took place in the physical form of the cities — from antiquity, through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and later from the turning point of the Industrial Revolution — urban furniture and design have also developed.

The Industrial Revolution led to the growth of existing cities and a significant increase in the number of cities, and with the urban populations growing rapidly from the beginning of the 20th century, the need for street furniture has grown and has been developed accordingly. The first example of street furniture as an industrial off the shelf product is the gas lamps which were used to illuminate the docks and streets throughout England in 1870. The same elements of lighting were designed from cast iron and represented the classic line of the period with intricate Gothic shapes. Another street furniture that became significant during that period is benches, mailboxes and traffic guides.

Small-scale generic monuments: the case of London, Berlin and Tel-Aviv

Despite their being of less importance than buildings, there are quite a few examples of street furniture which over the years have become an urban symbol. Unlike buildings, they were privileged to become a symbol not necessarily because of the monumentality, but just the opposite, because of their generic and replicated nature. These have become so popular that they even became a tourist attraction and a must-see "selfie" destination. One well-known example in western cities is the Red Telephone Box in Britain — public telephone stands set up as public service in central Britain and the former colonies of the British Empire from the 1920s, designed by architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. They soon became popular and even a symbol associated with British culture. In 2006 the Red Telephone Box was selected as one of the top ten design icons in the UK, and in 2017 it was even added to the UK National Heritage List.

Five K2 Red Telephone Box, Broad Court, London WC2, England (Credit — Nelson Rocha, 2009)

Naturally, the number of Red Telephone Boxes across the UK is declining due to the increasing use of cell phones. However, many of them continue to serve the public in other ways, and some are even undergoing restoration and preservation, due to their high popularity among the British public. In a world where globalization has dominated, there is a special rationale in elements that are identified with only certain cities, elements that mark the uniqueness of the city compared to countless other western cities which are more or less similar in their characteristics. In the western capitalist world, the uniqueness of Red Telephone Box also translates into a tourist value and therefore an economic value. Some of the Red Telephone Box have been converted for other uses, such as devices for selling postal items, public libraries and even ATMs. There may no longer be a need for phone booths but they are an icon and their heritage is just as important.

Another example of iconic street furniture is the 'traffic light man' from Berlin known as Ampelmännchen. This is a figure that was common at pedestrian traffic lights in East Germany in the 1970s. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the unification of Germany it became a common symbol in the west as well, and one of the positive symbols identified with the former communist state. The figure was designed by the traffic psychologist Karl Peglau following his investigation of road accident deaths in East Germany from 1955-1960. He concluded that the accidents were often caused because pedestrians were unable to see the traffic light properly, especially in wintry weather. His solution was the design of the Ampelmännchen, which has a wider and more prominent cut than the one that had appeared in traffic lights until then. Today it is one of Berlin's most recognizable emblems and Ampelmännchen memorabilia can be purchased in souvenir shops around the city.

Tel-Aviv: a young city without respect for its heritage

From a historical perspective, Tel-Aviv is a baby, only 111 years old. Since the early 20th century, when it was nothing more than a small neighborhood with a few streets and boulevards, street furniture already was placed in it. In the spirit of the time in Israel, the design of the furniture was minimal, simple and inexpensive. Over the years the city has grown to become the largest metropolis in Israel, and in recent decades, the municipality has decided on a new policy of street language — from uniform sidewalks, through a specific color palette in street design to the use of uniform street furniture throughout the city.

Ampelmaenchen in Berlin (Credit — Wikipedia)

Despite the positive attitude towards the treatment of public space in the city, the most unfortunate decision of the municipality recently, was their decision to replace the old street sign of Tel Aviv with a new model. For decades, those awkward and funny lightboxes, designed with the David font, is one of Tel Aviv's most recognizable icons — these street signs have become platforms for social protests, they were a cultural and artistic symbol and more than anything they were a symbol identified with the city's heritage. I am not claiming that these street signs are necessarily beautiful or sophisticated in their design, not at all, but they have always been there, engraved in the municipal DNA, and even enjoyed a renewed recognition, becoming an urban monument. Today, when these street signs are disappearing in favor of minimalist black and white signs, they can, in retrospect, be appreciated for their charm and their uniqueness: they have architectural qualities, and each sign looks like a miniature of a small Bauhaus building, befitting the White City.

A pile of the old street signs in Tel Aviv, Israel (Credit —Gil Harbagio Cohen, 2019)

The new street signs are like posters installed on existing lighting poles, without personality and any uniqueness in their design. The main reason for replacing the old street signs is the tendency to reduce the number of elements in the public space, which in itself is a positive idea, but the concern is that in this case, it is one of the wrong moves the municipality has made in recent years. Why? Because in an instant it has destroyed a long-standing heritage, a symbol and an urban icon in a relatively young city. The old street signs created continuity in the life of the city, they gained the patina of time and blended into the character of the city. In a world where everything is constantly changing, not everything needs to change, at any cost. Israel is a young society with little respect for its short history, and it seems that the dominant ethos is that everything is interchangeable. It can be done differently: renewal without erasing or ignoring the past, even if it is a bench and a trash bin.

Conclusion: Every bench has a name

The first step in preserving street furniture is the recognition of its importance, the identification of it as an essential, even if not spectacular, element in the design of the urban being. The second step is an examination of the street furniture that has become iconic, are identifiable with the city, are a tier in the urban heritage and are therefore worthy of preservation. The last step is to crack the way conservation should be done. Street furniture is inherently built from durable materials, well anchored to the ground to prevent theft and vandalism. They are inexpensive to build and the materials are usually easy to maintain. Similar to home furniture, street furniture is designed to address different functions and to create a certain aesthetic experience or atmosphere as well.

Preserving the street furniture is different from preserving buildings. There is no need to preserve all benches or bus stops, as this may be an absurd and ridiculous operation, but instead create conservation plans and general guidelines taking into consideration the past and the local heritage. Buildings are the main heroes of the city, no doubt. But between them are placed smaller, modest and almost imperceptible objects, and they play the role of supporting actors within the great urban narrative. These lightweight and often neglected objects affect our daily lives no less than the big building projects.

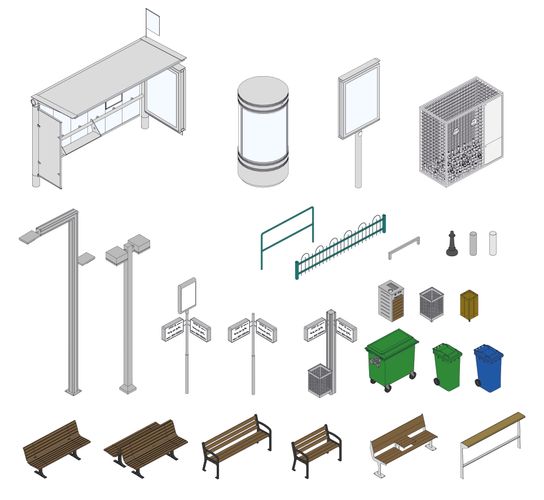

Illustrations of street furniture in Tel Aviv, Israel (Credit — Amnon Direktor, 2020)

The role of street furniture is first and foremost functional, but it is also a tool for creating an identity within the vast and sometimes chaotic organism called a city. As mentioned, of all the components of the urban landscape, street furniture is the one that maintains the closest contact and interaction with people, thus efficient and quality furniture in the public space creates an organic relationship between people and the urban landscape. It produces belonging and contributes to a sense of harmony within the urban chaos. Proper design, planning and preservation of street furniture are based on an in-depth reading of the urban history and local atmosphere, and at their best they make the life of the resident more comfortable. Similar to the feelings people develop towards certain buildings in the cities — the magnificent town hall, the building where they were raised, the school they went to, so do they develop an affinity for street furniture — the bench they sat on with their lover, the street sign with amusing graffiti.

The 21st century presents new requirements and challenges to our urban landscape. Influenced by the rapid urbanization and globalization processes, global warming and the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a greater importance to designing quality and healthy urban space. More than ever, cities around the world are investing a lot of resources in designing a quality design language that is also reflected thanks to its furniture. The future of street furniture includes complex designs and modern technologies, ecological and environmental thinking and no less important — the creation of objects that are comfortable to use and pleasing to the eye, that offers a safe and comfortable stay in the public space.

Amnon Direktor is an architect and journalist originally from Tel Aviv, Israel. He graduated in architecture from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. These days he is starting a master's degree in urban studies at the Free University of Brussels in Belgium. In recent years he has worked at Bar-Orian architecture office and Moria-Sekely landscape office. In addition, Amnon has been writing regularly in a number of magazines and journals on topics about architecture, urbanism, and city life.